Moral Distress in Anesthesia

Moral distress occurs when a clinician recognizes the ethically appropriate course of action but feels constrained from acting due to institutional, legal, or hierarchical barriers. In anesthesia, this phenomenon has received increasing attention, as anesthesiologists frequently work at the intersection of patient safety, surgical demands, and systemic pressures. Understanding the roots of moral distress in anesthesia is essential for both clinician well-being and the delivery of ethical, patient-centered care.

Anesthesiologists often encounter situations in which their professional judgment conflicts with external pressures. For example, they may believe a patient requires further optimization before surgery, but institutional or surgical team expectations push for proceeding. Similarly, inadequate staffing, resource shortages, or pressure to minimize delays can create tension between patient safety and productivity. Moral distress also arises in end-of-life contexts, such as providing anesthesia for futile procedures on terminally ill patients, or in cases where consent is unclear and time pressures limit meaningful discussions with patients or families.

Repeated exposure to moral distress can lead to emotional exhaustion, burnout, and feelings of professional disempowerment. In anesthesiology, the cumulative weight of unresolved moral distress may compromise attention and decision-making. Clinicians experiencing moral distress report frustration, anger, and guilt, particularly when they perceive that their concerns are dismissed by colleagues or administrators. Over time, this can breed disengagement, cynicism, or even attrition from the profession 1–3.

Beyond clinician well-being, moral distress can indirectly affect patient outcomes. When anesthesiologists are pressured to compromise on safety checks, consent processes, or postoperative monitoring, patients may be exposed to greater risk. Moral distress may also discourage advocacy, as providers learn to silence concerns rather than repeatedly confront barriers. Overall, in the end, the erosion of open communication undermines the culture of safety that anesthesia has historically championed 4–7.

Addressing moral distress requires both individual resilience and systemic change. On the individual level, ethics education, debriefing opportunities, and peer support groups can help anesthesiologists articulate concerns and process difficult experiences. Mindfulness training and wellness initiatives may also reduce the psychological toll. At the institutional level, fostering a culture of open dialogue remains critical—this includes creating forums in which anesthesiologists can voice safety concerns without fear of reprisal, incorporating ethics consultation services into perioperative planning, and ensuring that production pressures do not eclipse patient-centered decision-making. Leadership must also recognize that efficiency goals cannot come at the expense of clinician moral integrity 8–10.

Moral distress in anesthesia reflects the ethical complexities of modern perioperative medicine. It emerges when anesthesiologists are forced to act against their professional judgment due to systemic constraints or conflicting priorities. Left unaddressed, it undermines both clinician well-being and patient safety. By acknowledging its existence and fostering environments where ethical concerns are openly discussed and respected, institutions can not only support anesthesiologists but also strengthen the moral foundation of perioperative care.

References

1. Buchbinder, M., Browne, A., Berlinger, N., Jenkins, T. & Buchbinder, L. Moral Stress and Moral Distress: Confronting Challenges in Healthcare Systems Under Pressure. Am J Bioeth 24, 8–22 (2024). DOI: 10.1080/15265161.2023.2224270

2. Pathman, D. E. et al. Moral distress among clinicians working in US safety net practices during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed methods study. BMJ Open 12, e061369 (2022). DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-061369

3. Hartunyunyan, H. et al. The Impact of Moral Distress on Clinicians Treating Patients during the COVID-19 Pandemic and the Concurrent Armenian War in 2020: Implications for WHO – EMT Teams. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 37, s114–s114 (2022). DOI: 10.1017/S1049023X22002138

4. Spence, J., Indovina, K. A., Loresto, F., Eron, K. & Bailey, F. A. Understanding the Relationships Between Health Care Providers’ Moral Distress and Patients’ Quality of Death. J Palliat Med 26, 900–906 (2023). DOI: 10.1089/jpm.2022.0425

5. Locke, A., Rodgers, T. L. & Dobson, M. L. Moral Distress as a Critical Driver of Burnout in Medicine. Glob Adv Integr Med Health 14, 27536130251325462 (2025). DOI: 10.1177/27536130251325462

6. Orgambídez, A., Borrego, Y., Alcalde, F. J. & Durán, A. Moral Distress and Emotional Exhaustion in Healthcare Professionals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 13, 393 (2025). DOI: 10.3390/healthcare13040393

7. Safari, F., MohammadPour, A., BasiriMoghadam, M. & NamaeiQasemnia, A. The relationship between moral distress and clinical care quality among nurses: an analytical cross-sectional study. BMC Nursing 23, 732 (2024). DOI: 10.1186/s12912-024-02368-z

8. Morley, G., Field, R., Horsburgh, C. C. & Burchill, C. Interventions to mitigate moral distress: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies 121, 103984 (2021). DOI: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.103984

9. Koivisto, T., Paavolainen, M., Olin, N., Korkiakangas, E. & Laitinen, J. Strategies to mitigate moral distress as reported by eldercare professionals. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 19, 2315635. DOI: 10.1080/17482631.2024.2315635

10. Fantus, S., Cole, R., Usset, T. J. & Hawkins, L. E. Multi-professional perspectives to reduce moral distress: A qualitative investigation. Nurs Ethics 31, 1513–1523 (2024). DOI: 10.1177/09697330241230519

More From The Blog

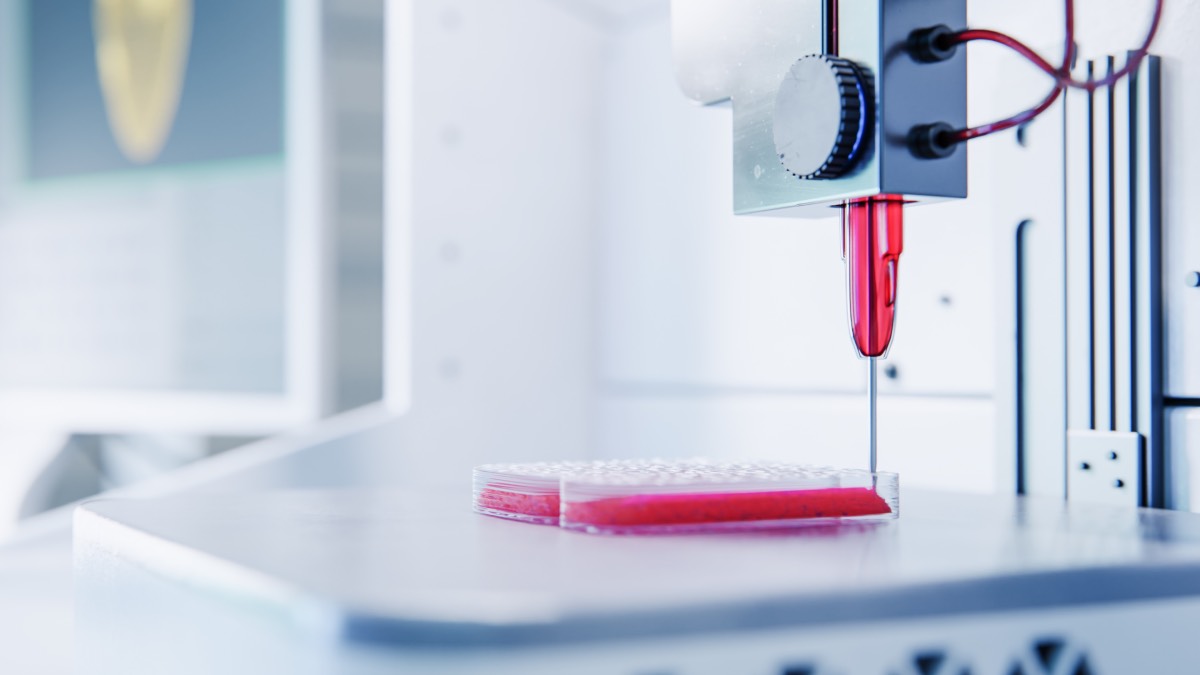

Bioprinting for Medicine

Bioprinting is an emerging medical technology that often captures public imagination, but it is important to understand both its promises and its present limitations. At

Reasons Against Using Remimazolam As An Anesthetic Agent

Remimazolam, a newer intravenous anesthetic agent, has gained attention in the medical community due to its unique pharmacological properties, such as rapid onset and short